In 2008 I got the chance to travel to Kodiak, Alaska for an entire summer of research on the red king crab. Researchers were concerned that global change would threaten an economically important and thriving fishery around the Aleutian Islands. The poles are warming faster than anywhere else in the world. In addition, waters are gradually becoming more acidic in a process called ocean acidification, which is caused by increased uptake of carbon dioxide in ocean waters. Ocean acidification was my specific area of research as an intern in Kodiak. I was responsible for trying to figure out the effect of acidified water on the young life stages of the red king crab. The assumption was in this area of the world, global climate change would cause problems for this cold-water species of crab. However, that is not the assumption everywhere in the world.

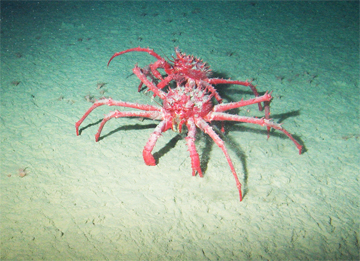

Some species benefit from warming waters. A large part of the Antarctic continental shelf (or the shallow waters that fringe the land mass that is Antarctica), is off limits to many species because it is simply too cold. In very cold places like Antarctica, the water at the ocean’s surface is actually colder than the deep water because the air temperature cools the surface water. So in Antarctica, many species aren’t able to live and grow in the shallow waters, even though they are abundant in the deep water offshore of the continental shelf. This is the case for many species of large crabs with crushing claws, that are abundant in the colder waters near the North Pole and Alaska, like king crabs. King crabs are the crabs of “Deadliest Catch” fame.

The shallow waters of Antarctica have been too cold for crushing crabs for 14 million years. As far as crustaceans on the Antarctic continental shelf go, currently there are only five shrimp species that are able to survive in the colder, shallower waters around Antarctica. The absence of large crab predators is very important to the bottom-dwelling critters in Antarctica. Large crabs not only tear apart and crush prey they find while foraging on the ocean floor, they also produce gashes and holes in the surface of the mud at the bottom of the ocean. This is a lot of disturbance. Since the shallow waters of Antarctica have been free of many crab and fish predators for so long, they have developed some of the most diverse communities of starfish, corals, and mollusks found anywhere in the world. More than half of all the species found on the Antarctic shelf are endemic to the area, meaning they are found nowhere else in the world.

The animals that live on the floor of the Antarctic shelf have evolved to withstand fairly constant conditions, with not much disturbance. The major predators of the Antarctic shelf are slow-moving predators like starfish and urchins. That means the clams, snails, corals, and other invertebrates that live on the Antarctic shelf are relatively unprotected: thin-shelled, slow-moving, and non-toxic. Examples include thin, almost translucent snails; fragile, fleshy gorgonian corals; meaty, lumpy clams that divers can collect by hand; and white nudibranchs (shell-less snails) that do not collect poisons from their food like their coral reef-dwelling cousins. These animals would likely not do very well if a new, relatively quick predator with crushing claws and pointy, probing feet were introduced onto the continental shelf. Which, of course, is exactly what is happening.

Sea surface temperatures on the west Antarctic Peninsula have risen about 1° C since 1950. Observations made by deep-sea submersibles suggested that this temperature increase may have been enough to allow king crabs to move from the deep water surrounding the Antarctic continental shelf, up the slope, and closer to the continental shelf itself. A team of researchers traveled to Antarctica to document king crab presence on the slope, and to see how close the crabs were to reaching the shelf. This video summarizes what they found.

King crabs were spotted on the lower portion of the continental shelf. Crabs were seen actively consuming starfish and other bottom-dwelling animals, and diversity of other animals was reduced in areas where crabs were abundant. An additional survey of the Antarctic continental shelf in 2012 revealed populations of king crabs in the deeper portions of the shelf itself. In fact, a team of researchers recently discovered a healthy population in a deep basin called Palmer Deep, 120 km away from the slope, indicating that the crabs can cross the shelf already. The amount of crabs found in Palmer Deep is greater than the commercially exploited populations present in Alaska and South America (per unit area). In Palmer Deep, the researchers never saw evidence of the four species of starfish that should have been in the area. They did see an estimated 100-300 punctures and gashes in every one-meter section of seafloor mud the robot camera covered. Wherever researchers found crabs, they also found evidence of crabs changing their environment.

If the current range of king crab in Antarctica is any indicator, current trends in warming suggest that king crabs will be a common fixture on the continental shelf in 100-200 years. This has led researchers to claim that king crabs are invading the Antarctic continental shelf. Are these crabs really invading? The question is not whether crabs will really become more common on the continental shelf of Antarctica, because they most likely will, but whether the term “invasion” is the best word for what is happening in Antarctica. “Invasion” has a very specific meaning to ecologists. According to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN), an invasive species is “an alien species which becomes established in natural or semi-natural ecosystems or habitat, is an agent of change, and threatens native biological diversity.” The uncertainty lies in the word “alien”, indicating the species comes from another place. It is difficult to tell how long crabs have been absent from the continental shelf. The fossil record is patchy at best, and scientists must rely on indirect cues, such as a fossil record of starfish that do not suffer from missing arms, which would have presumably been the case if crabs were around. Some would argue that lack of damage in fossilized starfish is not very reliable evidence. Are we just noticing more crabs on the shelf because we are spending more time looking? Have they been in Palmer Deep for much longer time than we expect?

Perhaps these crab species are undergoing a range expansion, driven by changing climate. This is expected to happen commonly around the world, as mobile animals such as fish gradually move to more suitable areas to follow changes in global climate. However, the range shift of king crabs may be more devastating for the ecosystem than a lot of other range shifts, because the Antarctic ecosystem has not experienced this kind of disturbance in many millions of years. King crabs will almost certainly be an agent of change, and a threat to biological diversity. The silver lining is that in this case, perhaps global change will create an economically important and thriving fishery for king crab on the continental shelf around Antarctica. With the remoteness of Antarctica, and the unstable weather conditions, it may be unlikely that such a fishery would ever attract investors or fisherman willing to take the risks. If it did, we better hope there will be a reality show, because this “Deadliest Catch” spinoff will be way more dangerous.

For more information:

Griffiths, H.J., R.J. Whittle, S.J. Roberts, M. Belchier, and K. Linse. 2013. Antarctic crabs: Invasion or endurance? PLOS One 8(7).

Smith, C.R., L.J. Grange, D.L. Honig, L. Naudts, B. Huber, L. Guidi, and E. Domack. 2012. A large population of king crabs in Palmer Deep on the west Antarctic Peninsula shelf and potential invasive impacts.

Sven, T., K. Anger, J.A. Calcagno, G.A. Lovrich, H. Pörtner, and W.E. Arntz. 2005. Challengin the cold: Crabs reconquer the Antarctic. Ecology 86(3):619-625. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 279:1017-1026.