From April 17th 2014 through May 1st 2014, the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has brought together a team of scientists and engineers to explore the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico using their ship, the Okeanos Explorer, and their remotely operated underwater vehicle (ROV) named the Deep Discoverer. To the delight of science lovers across the nation, NOAA has been streaming live camera feed from their ROV for anyone to watch, greatly reducing the productivity of marine scientists and nautical archaeologists. On Thursday April 27th the Okeanos Explorer visited two shipwrecks in the Gulf of Mexico (click here to see the highlights). They discovered a variety of “encrusting biology” (animals that live on the hard structures of shipwrecks), archaeological treasures, and even the chronometer (timepiece) and the octant (a navigation device) of the early 19th century ship, which has led me to coin my new favorite phrase for use when facing impossible odds, “It’s like finding an octant in a shipwreck.”

If you watched the feed from the Monterey C shipwreck, you may have noticed one major thing missing from much of the ship’s debris field- wood. Since wood from a shipwreck is pretty much the only organic material in such a harsh environment as the deep sea, a lot of the wood from the ship had long since been eaten away by animals that feed on wood. Wood is not an easy thing to eat. It is full of fiber and difficult for the gut to break down. Even animals that have special guts for digesting plant matter, such as cows and other ruminants, cannot break down wood. In the ocean there is one fairly common critter that can eat wood. They are called shipworms.

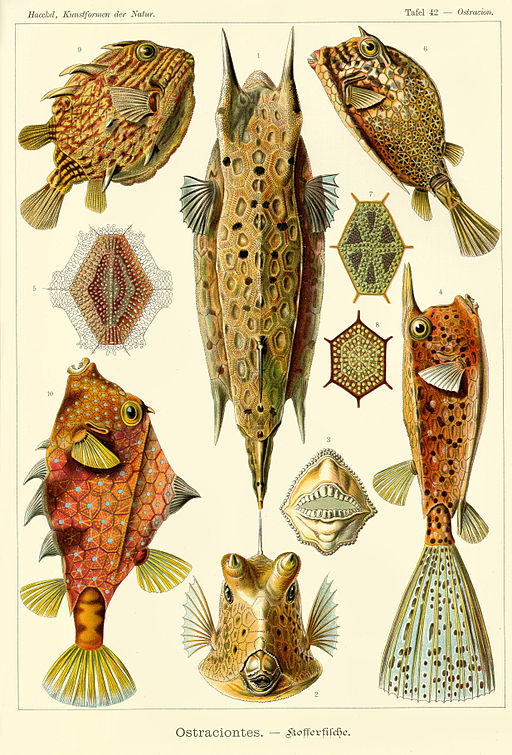

Shipworms are not worms at all. They are actually bivalves, a name that comes from the latin class Bivalvia. All of the members of the class Bivalvia have two (bi) shells (valves) that are hinged. Examples would be clams, oysters, scallops, and mussels. However, shipworms do not look like clams at all. They look more like worms, with long, fleshy, cylindrical bodies. They use their shells not for protection, like a clam or oyster, but to bore through wood. They can be a few centimeters long, or as long as a meter depending on the species, and they live in the burrows that they carve out of wood. The wood shavings are also consumed as food. The shipworm uses substances called cellulases to break down the wood, allowing them to extract nutrition from the tough fiber. This ability allows shipworms to join only a few known species that are capable of digesting wood, including protists, fungi, bacteria and a handful of species in several different invertebrate groups, including termites.

Just as termites can cause problems for homeowners, shipworms can cause problems for people whose livelihoods depend on the sea. Shipworms are responsible for destroying ships and piers around the world. They also eat shipwrecks, which in many parts of the world are an important part of history and heritage. The shipworm’s tendency to nibble away at nautical history means they are mostly viewed as pests that need to be eradicated. There are a few marine environments in the world where shipworms are not found. One is the Antarctic, which is protected from shipworms by the circumpolar currents which act as a barrier to shipworm movement. The Baltic Sea, which is too fresh for shipworms to survive, has been protected from shipworm feeding in the past. This shipwreck oasis is now in trouble because recently shipworms have begun to invade the Baltic. An eradication program has begun to prevent the shipwrecks from becoming mollusk food.

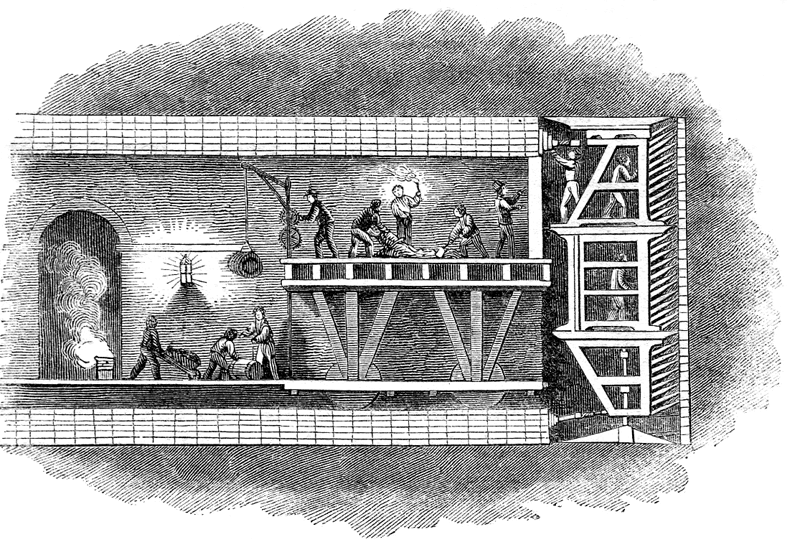

I understand the need to protect historical wrecks. However, far from considering shipworms as a pest, I propose we celebrate the shipworm as a genius. In fact, I suggest we award the shipworm an honorary degree in engineering. Here’s why. The shipworm has played a major role in helping humans discover solutions to two major engineering problems over the last two hundred years. Have you ever wondered what it takes to make a tunnel under a river? I know I have. Turns out it is not easy. Tunnels in soft sediment, like the mud under a river, tend to collapse as they are built. In the early 1800s, Marc Isambard Brunel solved this problem with a little help from the shipworm. He observed a shipworm’s tunneling behavior. The shipworm bores through the wood and as it makes its tunnel, it encases the tunnel walls in shell material to prevent the wood from swelling, closing the tunnel and crushing the worm. Brunel designed a tunneling shield, which was an iron cylinder that was pushed further and further into the tunnel as it was excavated, preventing the walls from collapsing in on the workers. In this way he was able to make the first tunnel under the Thames River, and it was all thanks to the shipworm.

A more recent example of the shipworm’s prowess as an engineer is the quest for the fuel that will replace fossil fuels. The energy crisis has led us to look at biofuels, or fuels derived from living organisms, such as plants. The production of biofuels involves collecting sugars from plants and fermenting those sugars to make ethanol. However, plants store glucose in a tough fiber called cellulose. Getting the glucose out of cellulose is costly, making biofuel production from plants costly as well. A lot of recent biofuel research has aimed at reducing the costs associated with removing glucose from plant tissue. I am sure you can see where this is going. Shipworms have already solved this problem by developing an association with bacteria that live in shipworm gills and digest cellulose. In fact, some shipworms appear to live off of wood alone, and do not grow any faster when provided with extra food. These bacteria are being cultured for use in biofuel production. Perhaps in a few years the shipworm will have helped us solve another complicated engineering problem, improving human lives.

Is the shipworm an irritant or an inspiration? Shipworms have experienced an interesting evolutionary path to fill a unique niche, and they have developed the ability to eat a substance that is extremely abundant, but useless as a food source for the vast majority of other animals. This path has unfortunately led the shipworm to torment ship-owners and owners of waterfront property. It has also led to some of the most amazing achievements in engineering in the last two hundred years. This is the reason I think the shipworm deserves an honorary degree in engineering, and I hope this interesting animal will continue to inspire the great thinkers of my generation as we tackle increasingly difficult environmental issues.

For more information:

Honein, K., G. Kaneko, I. Katsuyama, M. Matsumoto, Y. Kawashima, M. Yamada, and S. Watanabe. 2012. Studies on the cellulose-degrading system in a shipworm and its potential applications. Energy Procedia 18:1271-1274.

Asfa-Wossen, L. 2012. Tunnel vision. Materials World, 20(5):10.

Tanimura, A., W. Liu, K. Yamada, T. Kishida, and H. Toyohara. 2013. Animal cellulases with a focus on aquatic invertebrates. Fisheries Science 79:1-13.

Miller, R.C., and L.C. Boynton. 1926. Digestion of wood by the shipworm. Science 63(1638):524

Gregory, D. 2010. Shipworm invading the Baltic? The Nautical Archaeology Society 431.